written 7/7/10

In two weeks, I will officially be a mosadi mogolo. Mosadi mogolo means 'old lady' here, which is most definitely not a derogatory term at all here. Rather, it is used to show respect, or when applied to someone who is obviously not an 'old lady', to draw out a chuckle. Of course, I am not an old lady, but according to the official rules of the Mosadi Mogolo World Cup, I will qualify as one when I turn 25 in two weeks. This brings back a memory of 10th grade history class, when one of my classmates declared to the teacher that life pretty much ends once you turn 25- not knowing that the next day was the teacher's 25th birthday. Now it is my turn, and 25 does not sound old at all, and life had better not end for me in two weeks. All that will happen, I am quite sure, is that I will finally be able to rent a car and book any hotel room I want in the US, and apparently, I will become a mosadi mogolo here.

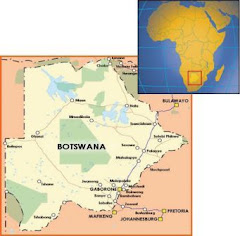

The Mosadi Mogolo World Cup is my first community event here in Botswana, and our entire sub-district is participating, with nearly every town, village, and catchment area represented. The event is run by our district health team, and it involves a World Cup football (soccer) series in which only women over 25 years old can compete. There are weeks of matches, which will culminate in a World Cup final in about 3 weeks. The score of the football match is not the only factor in winning the cup, however. After the match, each team faces off to prove their knowledge of HIV/AIDS and the PMTCT (prevention of mother to child transmission program) program. Their score on the quiz round is added to their score in the football match to determine the winner. The event was run last year, but this is the first year that my clinic has put together a team, which started holding practices on Monday. We are the definition of underdogs, with very little skill and not even enough players to fill all the field positions, much less the reserves. But we have heart. These ladies, ranging in age from 25 to older than 60, show up for an HIV/AIDS study session every day from 2-3pm, and then practice from 3-5pm. They have a coach who runs drills and urges them to “kick with power”. It is a pretty funny sight, to see all these women of various ages and states of physical fitness running and kicking across the field, with their small children trailing after them laughing and imitating. I've never seen anything quite like it, but I admire them. They are serious during the study sessions, and ask questions about difficult English words like 'cryptococcal meningitis' and 'immunodeficiency', and they seem to really enjoy themselves out on the field. I hope they do well in our first match, which will be held on Sunday.

A few entries ago, I was explaining, and almost lamenting, that I didn't have a lot of activities to fill my days with. This has changed drastically in a very short time. Now I have all sorts of demands on my time, and I wonder how I will be able to keep this up once I really start working on projects. My clinic is demanding more and more of time as the H1N1 campaign rolls forward. As many as 50-60 people will show up in one morning to get the vaccine, and for an already understaffed clinic that also must attend to every other health need the community has, the situation can become overwhelming quickly. I am not allowed to administer vaccines, but just collecting the charts and documenting the vaccines takes a bit of the pressure off the nurses. I also answer the phone (although I don't think this helps much- Setswana is tough enough for me to understand in person, let alone on the phone, and I always have to get someone else anyway), find lab results, and count pills (but I don't distribute them, as that would be another big no-no for a PCV). The clinic is chaotic and crowded in the mornings, but empty and sleepy in afternoons, so I think if my clinic had its way, I would be there every morning. Of course, Botswana is a very morning-oriented country, so every other organization or school I want to meet and work with also wants me to come in the mornings- and there's only so many places I can be at once! To my clinic's dismay, I spent the first hour of the morning today at the local primary school, and I will be spending the entire day, morning included, at the senior secondary school. I understand that the clinic is busy and needs extra hands, but at some point we need to compromise. Peace Corps volunteers are supposed to be working on capacity building projects and community programs and education, not doing simple tasks that anyone can do and that the clinic staff will have to do on their own once the volunteer leaves. It's like hiring a teacher, but keeping her in the back office making photocopies. Of course I'll do the smaller tasks too. The clinic needs help with them, and I'm here to help. I'm not above it. But it's not all I should be doing. My primary job should be promoting the clinic's agenda and message out in the community and in the schools, and working within the clinic to help it provide better service to its patients. Putting stickers in charts is important, but not something to spend 20 hours a week doing.

Along with the needs of the clinic, the meetings I have had in the last couple weeks are slowly turning into real demands on my time. As I noted in previous entries, the secondary school is going to take a lot of my time, probably almost as much as the clinic. Yesterday, a man from the technical school stopped by the clinic to ask if I could help out with some life skills and health education issues, and I am waiting for his call to set something up. And today I spent part of my morning at a local primary school, and it looks like I will be spending a significant part of my time there, too. The kids range in age from 6-15, and although I will primarily be working with the guidance teacher on life skills and health, I'll probably also be helping out the teachers with their lessons, especially the English teachers. I was introduced to the entire school this morning, which was quite an experience. At the beginning of every day, the kids gather in lines according to age group in front of the school for the 'assembly'. Once gathered, they sing several songs (mostly religious, as is common anywhere in Botswana- it's also co-run by the Catholic church, so it makes even more sense here), and are spoken to by the headmaster, the guidance teacher, and a nun (also a teacher). Parts of these speeches seemed to be a practiced dialogue, and the kids knew all the responses. Because this is a primary school, everything was in Setswana, so I didn't really get a lot of it. After the speeches, it was my turn. As usual, I was introduced as being from the UK. Apparently the people here don't recognize accents well, because I've been told that I am from England, Australia, and South Africa- anywhere that there is an abundance of white people. Today at the clinic, I was told that I have a European voice. When I corrected the teacher and told the kids that I was from America, I got a collective awed gasp from my audience, followed by a louder one when I said that I was from New York. New York is one of the few American cities that everyone here recognizes, and I always get a good reaction when I tell people I lived near there. I blame Jay-Z, since I can't get through two days here without hearing “Empire State of Mind”. Anyway, the kids were very attentive, even if they were a bit giggly, and soon my part of the show was over. They sang a couple more songs, and were dismissed. Even the dismissal was orchestrated- the kids peeled off in their lines row by row while singing “We Are Marching in the Light of God”, and headed off to class. I stuck around and met the teachers, who seemed unconcerned that all of their students were sitting in their classrooms unattended while they were introduced to the strange American. After our meeting, I entertained the guidance teacher's class for a few minutes before heading back to the clinic while she attended to something. The kids in the class were 7 and 8 years old, and their English skills were minimal, so we were a bit limited. I taught them the word 'map' and drew one to show where I was from, and had them point out Botswana. Classes for this age are usually taught in Setswana, but when they are older, they will be taught in English only. This seems a little strange to me, almost like the kids are set up to fail. Some kids don't even speak Setswana at home. In Mahalapye this is less of a problem, but in some parts of the country, many people speak Kalanga or Sesarwa or Afrikaans at home. As one PCV put it on her blog (this won't be exact, but it was a good example), imagine growing up speaking English at home, but then starting school at age 6 and being taught in Spanish only. You are then taught French using Spanish, and when you hit high school, you are expected to learn everything else- science, math, history- in French, your third language. It would get a little confusing, to say the least. I can't imagine having to do it, but I'm impressed at how well these kids adapt to it. I'm having trouble just learning Setswana! I'm waiting for the guidance teacher's call to find out when I'll be headed back, to help out on a regular basis, but I think it will be soon.

Not only do I have these schools and my clinic playing for my attentions, but I'm also supposed to be doing my community assessment, and I still haven't met with even half the groups that I wanted to meet with. I also still have to make it over to the hospital and the prison, even if it's just to find out more about their services and their connection to the community as a whole. I'm just going to take it week by week for now. I have plenty of time before In-Service training at the end of August, and even more time before my term of service in Botswana is over. As I was standing this afternoon with the sun beating down on my head, watching my mosadi mogolos running down the field through the dried grass and into the deep blue sky, the woman organizing the team mentioned that she hoped for a better team next year. I looked at her and agreed that next year we would have enough time and experience to pull together a very strong team- and then realized what I said. I will be here next year. I'm not just passing through, and I am not just a visitor. I don't have to get everything done in the next few weeks, because my departure is not imminent. I live here, and this is my community. I'm not staying forever, but I am staying. It's not something that I can come to terms with yet in the evenings, when often all I can think about is home and family and friends, but there in that field today, I accepted it without thinking. I will be here next year.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment