written 6/23/10

Her name is Eva*. She is 43 years old, younger than my parents, and she is the mother of 5 children, although none are at home today. When I first walk into the darkened one room cement house where she is staying on her mother's compound, I see nothing but a pile of blankets spread over a thin foam mat on the floor under a small window. Her mother calls her name, and the pile of blankets shifts slightly, and a gaunt face with large, sunken eyes and high cheekbones appears. She has no hair, and she has difficulty keeping her eyes open for more than a few moments. She responds to her name with a murmur, and closes her eyes, using what little strength she has to bury her face in her pillow. Her mother pulls aside her blankets to show us legs that are no more than skin-covered skeleton. She gently moves her daughter's legs to avoid bedsores, and we see that she is wearing an adult diaper. Her emaciation is breath-taking. She cannot weigh more than 70 pounds, and that is a generous estimate. I have never seen disease and suffering like this in person, and it is difficult not to allow my emotions to take over. My instinct is to sweep her up in my arms and rush to the nearest hospital, demanding immediate attention, IV nutrition, and medication. Fighting this urge, I listen as her mother sits on the floor next to her and calmly tells us that she did in fact spend Monday in the hospital due to severe diarrhea, and was discharged with a diagnosis of wasting syndrome, some medication, and a can of Ensure, on which she has been subsisting exclusively. For several days last week, she refused food altogether, and was unresponsive and not breathing properly. It is difficult to believe that the condition I am seeing her in now is actually an improved condition. According to her mother and her medical chart, she had been on ARV's for some time, but stopped taking them regularly for an unknown amount of time. As is often the case, this break allowed for drug resistance to build, and although she has restarted treatment, it is no longer effective. She has finished rounds of tuberculosis drugs, but her mother still piles startling quantities of daily medications on our laps when we ask what she is taking. There are enough drugs, she says, but she is nearly out of diapers and Ensure and other supplies necessary for her daughter's care. She pauses to turn her daughter's legs once again, and we notice discoloration on her feet that may be the first signs of Kaposi's sarcoma. It is strange to note how calm everyone is, when everything inside me is screaming. Don't they understand how serious this situation is? How can life go on for this family with their loved one suffering on a foam mat?

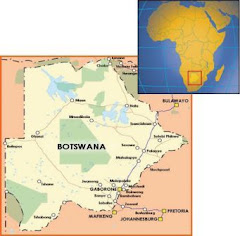

Of course they understand the gravity of the situation. Of course they are grieving, and of course they care. However, it is a fact of life for them, something they must find a way to deal with every single day, as it is for so many here in Botswana. I am the newcomer here, who, despite my outrage and empathy, will walk away at the end of the visit and go on with my life as usual. Who am I to judge them for going on with their lives? Despite their apparent calm and good cheer, it is obvious the toll it is taking on the family. They greet me with smiles and warmth, but talk seriously about Eva's illness. Her older sister sits next to me outside, and with a wry smile and a shake of her head, she sighs and looks at me intently. “I'm tired,” she says, “so tired.”

Soon it is time to leave, and we advise her mother to put the radio on in her daughter's room so she can have something to occupy her mind, as she is too weak even to read, and we promise to return soon, hopefully with extra supplies. I find it difficult to leave, and I spend much of the walk home memorizing the path so I can find it again, although I have no idea how I could possibly help. As I get farther and farther away, perspective begins to return, and I realize that I cannot single-handedly swoop in and save anyone through sheer determination and will. This is not to say that I won't be back- I have no doubt that I will be, as part of the community outreach of my clinic. But I do have to remember that there are doctors and nurses who are doing the best they can, and allow myself to understand the grave reality of HIV. Until now, HIV has been an abstract idea for me, and many people, I allowed myself to live in the fantasy that ARV's have somehow emasculated HIV and made it more of a nuisance than a serious virus with no cure. Of course, ARV's have made an enormous difference, and every day they allow people to live out healthy lives for years and years longer than they would have without them. But they are not a cure, and people still die from AIDS. I think of all the young people I have seen at the clinic in the last few days, vibrant, healthy, laughing- and then I think of how many of them are HIV positive. And how many of them are mothers. Will they suffer like Eva? The thought is unimaginable, unbearable, but it is more than plausible. Do they know what could possibly be lying ahead for them? And what about those that are negative for now, but engaging in unsafe sex? Do they know what they are really risking? Until today, I didn't really know. Until today, HIV was a virus, clinical and impersonal, and AIDS was something people only died of in movies. Today I saw the face of this disease, and it was real, and the image will stay with me for the rest of my life.

On our way back from Eva's house, we meet another face, a small boy no older than 6 years old and already HIV positive. He is playing in the yard with his brother, and runs over to the fence to greet us, although he turns shy when he sees me. He puts his hands together as if in prayer, and pushes them through the fence toward us, a traditional sign of respect that few children here remember these days. We take his hands briefly, and he retreats back to stand near his giggling older brother, staring back at us with wide, curious eyes. His mother isn't home, so we will return for a visit another time, as he, too, is a patient at our clinic. This small boy, like so many others, will grow up HIV positive through no fault of his own, taking powerful drugs every day for the rest of his life, and may never know why. Certainly he doesn't understand it now. Maybe by the time he is old enough to understand, we will have found a cure, or at least a new line of drugs that will allow him to lead a long, healthy life, and he will never have to know suffering like Eva's.

Maybe.

*Name has been changed to ensure privacy.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment